Bone marrow transplantation celebrated the completion of 43 years this year[1]. In last four decades BMT has established itself as the only definitive cure for a number of blood disorders. In India, the BMT program is 30 years old and the first transplant dates back to 1983 which was done at Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai[2]. Over the last two decades the treatment protocols across the globe have matured and the survival rates of people undertaking transplants has substantially improved[3,4]. It would be fair to say that neither is transplant a new science nor is it an unknown area in modern medicine. A country like ours has thousands of deaths associated with blood disorders that are curable by transplants. In this scenario, one would expect hundreds of BMTs happening each year in order to save the precious human lives - and in this particular context - majority of the patients are little children. Nevertheless, the facts are disturbing and alarming to say the least. There are less than 100 beds for transplant across India, several of which are catering to the international patients. In-spite of the fact that way back in 2005 a multicenter study identified the need to develop more transplant centres with adequately trained personnel[5], growth, especially in public health care setups is very slow. If we were to do equivalent transplants to those done in Europe, we should have been doing 13,500 allogenic tr ansplants and 19,000 autologous transplants a year[6]. Compare this with the number of transplants each year not crossing the 3 digit mark in our country so far. The option of cure, in-spite of being feasible, is not available to most of the people who need it.

Let us discuss transplants in the context of thalassemia. Estimates say that about 12,000 children[7,8] are born with thalassemia each year in our country. WHO data shows that 90% individuals born with thalassemia have no access to treatment in our region[9]. Facts are speaking for themselves. Mortality associated with thalassemia is extremely high in our nation. Over the last four years Sankalp India Foundation has actively involved itself in Thalassemia management and care. Anyone who is involved with management of children with thalassemia would know now that even those few individuals who are getting proper management and care are exposed to untimely death. Infections associated with blood transfusion, iron overload, cardiac complications and other complications which result from the inevitable splenectomy (which are done for chronically transfused patients) result in loss of numerous lives. We are still measuring the survival associated with thalassemia in our nation. There is hardly any focus on the quality of life of the individuals who are under chronic treatment therapy. The high costs, the need to visit the centres for transfusions and consequent disruption of normal life, the complications associated with thalassemia, the side effects of the various drug therapies, poor growth and in many places the struggle to get access to blood - all of this severely impacts the quality of life of the patients. Though it's true that very rarely we are beginning to celebrate the marriages for the individuals with thalassemia, the promise of near normal life for a person under chronic management of thalassemia is far from true.

One third of the thalassemia patients are expected to have matched sibling donors. So, why is it that the curative option - Bone Marrow Transplant has not taken off as much as one would expect it to? Let us examine the associated factors one by one.

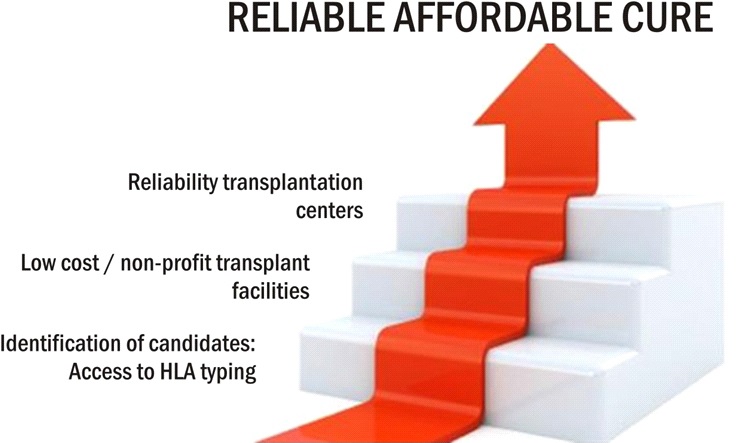

Cost of transplant has been the single biggest inhibitor to the increase in the number of transplants in the country which hovers as around INR 15,00,000/- upwards in most centres. The cost makes the option of transplant infeasible for most of the patients. The more damaging impact of the cost of transplant is its impact on patient selection. With such high costs, the selection of patients for transplants is not on the basis of medical fitness but rather on the basis of financial condition of the family. Published outcomes of the transplants in our country clearly indicate that there are more patients from the higher risk groups of transplants who are selected for the procedure[5]. Higher risk of transplants leads to poorer outcomes - something which adversely impacts the confidence of the administrators, patients and public at large in the procedure itself.

Another major problem is the adoption of certain practices which are unscientific and contrary to evidence and yet which cause significant cost escalation. An example of this is the almost universally adopted practice of positive air pressure and hepa-filtered set-up even for non-malignant low risk transplants adding significantly to the cost of the process. The irony is that there is hardly any study indicating the association of mortality of patient with the absence of these complex systems. Rather there is plenty of evidence to suggest that in the absence of such complex systems excellent outcomes have been achieved[10-13]. Another ironic fact about the whole issue of cost is that Cure2Children experience has scientifically proven that transplants with outcomes comparable to the developed countries can be done in the developing world at a cost of about INR 6,00,000/-[10-12,14].

The fact that the number of fully operational allogenic bone marrow transplant units in public healthcare set-up or in non-profit setup in our country can be counted on finger tips explains why costs never came down and BMT did not scale up as much as it should have.

With the cost of transplant being equal to the cost of few years of disease management in our country (estimated cost of a year of thalassemia management is Rs. 1,80,000/- to Rs 2,40,000/-[15]) purely from economic point of view, it would have been a wise decision on the part of public health policy to promote transplants. We have also suspected the influence of industry in ensuring that the spotlight on chronic management involving their products rather than cure.

Cost apart, the argument of safety of transplant and the chances of mortality seem to have played heavily on the minds of the stakeholders. Contrary to the available scientific evidence and expert consensus[4] still there are those individuals who consider transplant as an unworthy match to management of thalassemia. The assessment of mortality associated with thalassemia management at any centre which is working for a significant number of years will in itself prove that transplant associated mortality is much lesser. We are happier letting our children wither away after years of agony and pain with extremely bad quality of life while they still fight the battle against thalassemia rather than take a reasonable chance of curing the child.

Having said this, we must admit that the survival associated with thalassemia varies from centre to centre. The transplantation in India is so far individual doctor driven. No centre in the country is accredited[16]. Protocols and procedures vary across the country. There is very little scientific sharing of overall outcomes. Often the level of fame of the hospital - even if it is because of a different speciality, the extent of marketing and the degree of sophistication showcased is used as a yardstick to select the centre rather than focus on the simple yet more sensible aspects that transplant outcome and survival of patients. The good news is that there are centres which frequently publishing their outcome, participating in international networks for greater standardization and more rigorous consultations and which are focussing on building transplants programs in-line with the requirements of international accreditation - something which will enable the curative option to gain reliability [2,5,11,12,17,18].

While the country battles to get over the problems and while progress is being made at faster pace in recent times, each day wasted is a life lost. It's also strange how BMT is being undervalued as an option just because it may not be available to all the patients[19]. What is appalling is the fact that while thousands of Indians are being screened free of cost for HLA type in hope of helping someone in future, there are those tens of thousands who continue to live with matched sibling donors with the HLA test out of their reach. We are extremely aggrieved with the rich centric approach of modern BMT in India and the failure of the state and the community to give thousands of children access to known, well established cure. We are agonized with the rampant commercialization of modern healthcare and the failure of the public healthcare to keep abreast with recent advances in medicine. As the focus of the Government on non-communicable diseases is increasing we hope to see better policy and greater focus on the most vulnerable population.

Sankalp India Foundation is focussing on ensuring that the option of affordable transplant is available for the children suffering from thalassemia within India at centres which align well with international best practices in transplantation and thereby offer reliable cure. Our partnership with Cure2Children, Italy is enabling us to get world class consultation and transplantation options for our patients. The vast gap between the number of available beds for transplants and the number of patients who await a cure is a challenge which we aim at meeting head on and find the way forward.

There is some food for thought that we would like to leave the readers with. There is significant push given to stem cell registries - where each HLA typing has a small chance of helping someone in future. Massive public movement is being created for the same and funds are being poured in. Even as this happens, families who have a good chance of a matched sibling donor continue to pay fully for HLA typing and thus find the test inaccessible. Why?