The All India Muslim League (AIML) was formed in Dhaka in 1906 by Muslims who were suspicious of the Hindu-majority Indian National Congress. They complained that Muslim members did not have the same rights as Hindu members. A number of different scenarios were proposed at various times. Among the first to make the demand for a separate state was the writer/philosopher Allama Iqbal, who, in his presidential address to the 1930 convention of the Muslim League said that a separate nation for Muslims was essential in an otherwise Hindu-dominated subcontinent.

The All India Muslim League (AIML) was formed in Dhaka in 1906 by Muslims who were suspicious of the Hindu-majority Indian National Congress. They complained that Muslim members did not have the same rights as Hindu members. A number of different scenarios were proposed at various times. Among the first to make the demand for a separate state was the writer/philosopher Allama Iqbal, who, in his presidential address to the 1930 convention of the Muslim League said that a separate nation for Muslims was essential in an otherwise Hindu-dominated subcontinent.

The Sindh Assembly passed a resolution making it a demand in 1935. Iqbal, Jouhar and others then worked hard to draft Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who had till then worked for Hindu-Muslim unity, to lead the movement for this new nation. By 1930, Jinnah had begun to despair of the fate of minority communities in a united India and had begun to argue that mainstream parties such as the Congress, of which he was once a member, were insensitive to Muslim interests. The 1932 communal award which seemed to threaten the position of Muslims in Hindu-majority provinces catalysed the resurgence of the Muslim League, with Jinnah as its leader. However, the League did not do well in the 1937 provincial elections, demonstrating the hold of the conservative and local forces at the time. The 1937 election resulted in a major shift in Indian politics; the Congress won in seven provinces and lost in four. The Congress success worried the Muslims. Jinnah grasped this moment and suggested that Muslims would be left to contend with a Hindu government after the withdrawal of the British. He stated that "Hindu Congress" was "putting Islam in danger".

The Muslim League gained power also due to the Congress. The Congress banned any support for the British during the Second World War. However the Muslim League pledged its full support, which found favour form them from the British, who also needed the help of the largely Muslim army. The Civil Disobedience Movement and the consequent withdrawal of the Congress party from politics also helped the league gain power, as they formed strong ministries in the provinces that had large Muslim populations. At the same time, the League actively campaigned to gain more support from the Muslims in India, especially under the guidance of dynamic leaders like Jinnah.

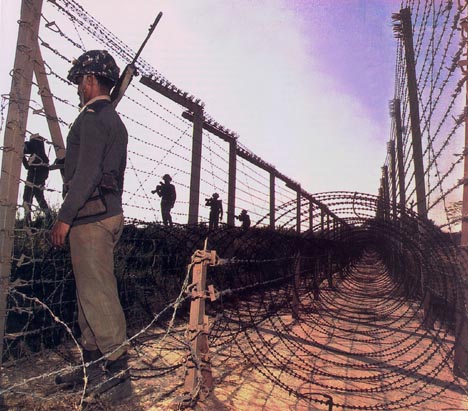

In 1940, Jinnah made a statement at the Lahore conference that seemed to call for a separate Muslim 'nation'. However, the document was ambiguous and opaque, and did not evoke a Muslim nation in a territorial sense. This idea, though, was taken up by Muslims and particularly Hindus in the next seven years, and given a more territorial element. However, while the Indian National Congress was calling for Britain to Quit India, the Muslim League, in 1943, passed a resolution for them to Divide and Quit. There were several reasons for the birth of a separate Muslim homeland in the subcontinent, and all three parties-the British, the Congress and the Muslim League-were responsible. The British had followed a divide-and-rule policy in India. Even in the census they categorised people according to religion and viewed and treated them as separate from each other. They had based their knowledge of the peoples of India on the basic religious texts and the intrinsic differences they found in them instead of on the way they coexisted in the present. Politicians and community leaders on both sides whipped up mutual suspicion and fear, culminating in dreadful events such as the riots during the Muslim League's Direct Action Day of August 1946 in Calcutta.

The 1946 Cabinet Mission was sent to try and reach a compromise between Congress and the Muslim League. A compromise proposing a decentralized state with much power given to local governments won initial acceptance, but Nehru was unwilling to accept such a decentralized state and Jinnah soon returned to demanding an independent Pakistan. Soon an alternative plan to divide the British Raj into a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan was proposed. The Congress rejected the alternative proposal outright. Muslim League planned general strike on 16 August to protest this rejection, and to assert its demand for a separate Muslim homeland.

The protest triggered massive riots in Calcutta, between supporters of the Muslim League and the Indian National Congress. In Calcutta, within 72 hours, more than 4,000 people lost their lives and 100,000 residents in the city of Calcutta were left homeless. Violence in Calcutta sparked off further religious riots in the surrounding regions of Noakhali, Bihar, United Province (modern Uttar Pradesh), Punjab, and the North Western Frontier Province. These events sowed the seeds for the eventual Partition of India.